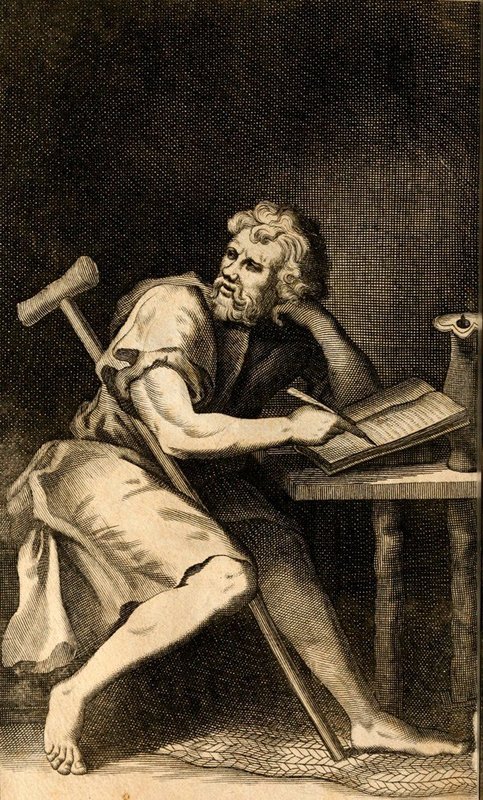

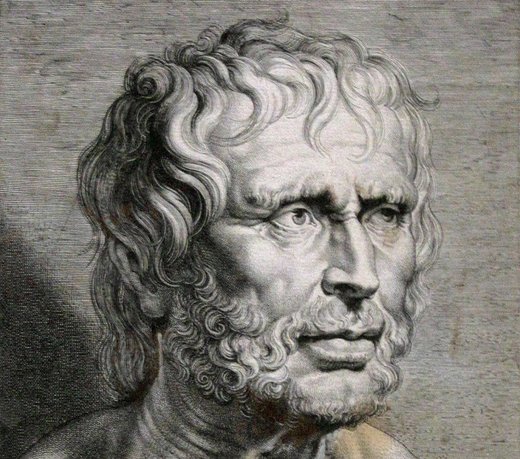

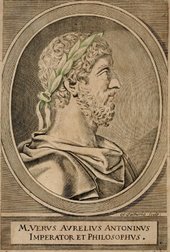

Stoicismens brede appel og anvendelse afspejles i forskelligheden blandt de, der gav anledning til den og dets tidlige fortalere - en romersk kejser og militærleder, en berømt skuespilforfatter, en tidligere slave, der blev fri og formede sig selv til at blive en fremstående taler, en succesrig handelsmand og en tidligere bokser, som finansierede sin skolegang ved at arbejde som vandbærer. Gennem årtusinder, har stoicismen fortsat med at øve indflydelse på sind så forskellige som Ralph Waldo Emerson, Martha Nussbaum, og Tim Ferriss. I dag er stoisk visdom så gyldig og styrkende som altid - Marcus Aurelius' råd om hvordan man skulle begynde dagen er en stærk recept på sundhed i den moderne verden. Senecas meditation om hvordan man kunne strække livets korthed ved at leve bredt snarere end længe, forbliver den største trøst over for kendsgerningen om, at vores liv er endeligt. Hans råd er den mægtigste modgift mod frygt, og fortsætter med at styrke vores ånd. Epiktet' forestilling om selvanalyse anvendt med mildhed er måske den bedste holdning vi kan dyrke overfor os selv og den sikreste strategi for sand vækst.

Kommentar: Delvist oversat af Sott.net Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius - timeless stoic philosophy that is essential to the human spirit

In The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living (public library), Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman reclaim this ancient school of thought from the sapping grip of academia and mend its misuses in the hands of popular culture to reveal its timeless wisdom in navigating the modern expressions of perennial human problems: how to love and how to work, how to tame and transcend anger, greed, jealousy, and the rest of our wildest flaws, how not to let success and power enslave us, how to find warmth and aliveness in the chilling awareness that we are mortal.

Holiday and Hanselman write in the introduction:

One of the analogies favored by the Stoics to describe their philosophy was that of a fertile field. Logic was the protective fence, physics was the field, and the crop that all this produced was ethics — or how to live.Holiday and Hanselman reap the fruits of that field in original translations of the late Stoic triumvirate — Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius — and some of the philosophy's earlier proponents. Their selections are temporally and thematically organized across the twelve months: from clarity in January and the passions in February to acceptance in November and mortality in December. For each day of the year, Holiday and Hanselman highlight a passage from one of the great Stoics and discuss its meaning in relation to daily life. Partway between Tolstoy's Calendar of Wisdom and Joanna Macy's A Year with Rilke, what emerges is a generous gift of guidance on modern living culled from a canon of wisdom hatched long ago and incubated in the nest of civilizational time.

The year begins with Epictetus's insight into control and choice, which opens the month of clarity under the entry for January 1:

The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control. Where then do I look for good and evil? Not to uncontrollable externals, but within myself to the choices that are my own...In another January entry, Seneca echoes the sentiment in a passage from his treatise on the shortness of life:

How many have laid waste to your life when you weren't aware of what you were losing, how much was wasted in pointless grief, foolish joy, greedy desire, and social amusements — how little of your own was left to you. You will realize you are dying before your time!Marcus Aurelius offers the three ingredients of the sane and satisfying life:

All you need are these: certainty of judgment in the present moment; action for the common good in the present moment; and an attitude of gratitude in the present moment for anything that comes your way.In a sentiment that calls to mind pioneering biochemist Erwin Chargaff's case for the poetics of curiosity, Epictetus cautions against fetishizing knowledge, suggesting that the moment the mind is made static in knowing, knowledge becomes an end point of curiosity and thus a stunting of growth:

If you wish to improve, be content to appear clueless or stupid in extraneous matters — don't wish to seem knowledgeable. And if some regard you as important, distrust yourself.Seneca admonishes against the destructiveness of anger:

There is no more stupefying thing than anger, nothing more bent on its own strength. If successful, none more arrogant, if foiled, none more insane — since it's not driven back by weariness even in defeat, when fortune removes its adversary it turns its teeth on itself.Epictetus points to the self-defeating impulse to want too much:

When children stick their hand down a narrow goody jar they can't get their full fist out and start crying. Drop a few treats and you will get it out! Curb your desire — don't set your heart on so many things and you will get what you need.In a passage reminiscent of Dr. King's famous dictum that "we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality [and] whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly," Marcus Aurelius reminds us that our own experience is inseparable from the experience of everyone and everything else:

Meditate often on the interconnectedness and mutual interdependence of all things in the universe. For in a sense, all things are mutually woven together and therefore have an affinity for each other — for one thing follows after another according to their tension of movement, their sympathetic stirrings, and the unity of all substance.The remainder of The Daily Stoic mines the ancient canon for practical wisdom on such facets of character as transcending fear, mastering the art of leadership, and using self-control as a tool of freedom rather than restraint. Complement it with the great humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm's classic treatise on the art of being, Oliver Sacks on the measure of living and the dignity of dying, and Susan Sontag on what it means to be a moral human being.

Læserkommentarer

dig vores Nyhedsbrev