Der er nu godt belæg for læsnings terapeutiske effekt. Projektet Shared Reading, organiseret af Reader Organisation anbefaler at læse i grupper - i deres tilfælde bringer de mennesker sammen i grupper, som har mentale sundhedsproblemer for eksempel, men resultaterne gælder lige så vel for den lokale bogklubs månedlige samling omkring et glas vin - som i betragtelig grad "øger selvtillid og selvværd, bygger sociale netværk, udvider horisonten og giver folk en oplevelse af tilhørsforhold, opretholder den mentale og fysiske sundhed hos de som er raske og opbygger mental modstandsdygtighed".

Chronic loneliness and isolation are now prevailing social problems, but it is not necessary to be part of a group reading project for a book to have a role in ameliorating this social malaise. As the shrewd and alienated Holden Caulfield says in JD Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye: "What really knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it." I think many of us can count some books as close friends (my particular friends are Henry James's The Portrait of a Lady and Patrick White's Riders in the Chariot). And it is by no means a trivial good that, at a fundamental level, reading confers a benefit by entertaining us. To "entertain" means to "admit, cherish, receive as a guest" and books can, and do, dissolve social isolation, as the estranged and damaged Caulfield exemplifies, by inviting in the reader to become involved in an imaginal world. Immersion in a fictional society seems to promote many of the rewards of immersion in actual society: among other benefits, it encourages escape from the self, by no means always escapist. To get outside the confines of our individual egos is a liberating experience, and entry into another universe, by way of the written word, may be a safer, or more practically possible, route for some - for the elderly, the incarcerated or the emotionally fragile, for instance - than by personal physical encounter. Among the Shared Reading successes is its work in psychiatric hospitals and prisons.

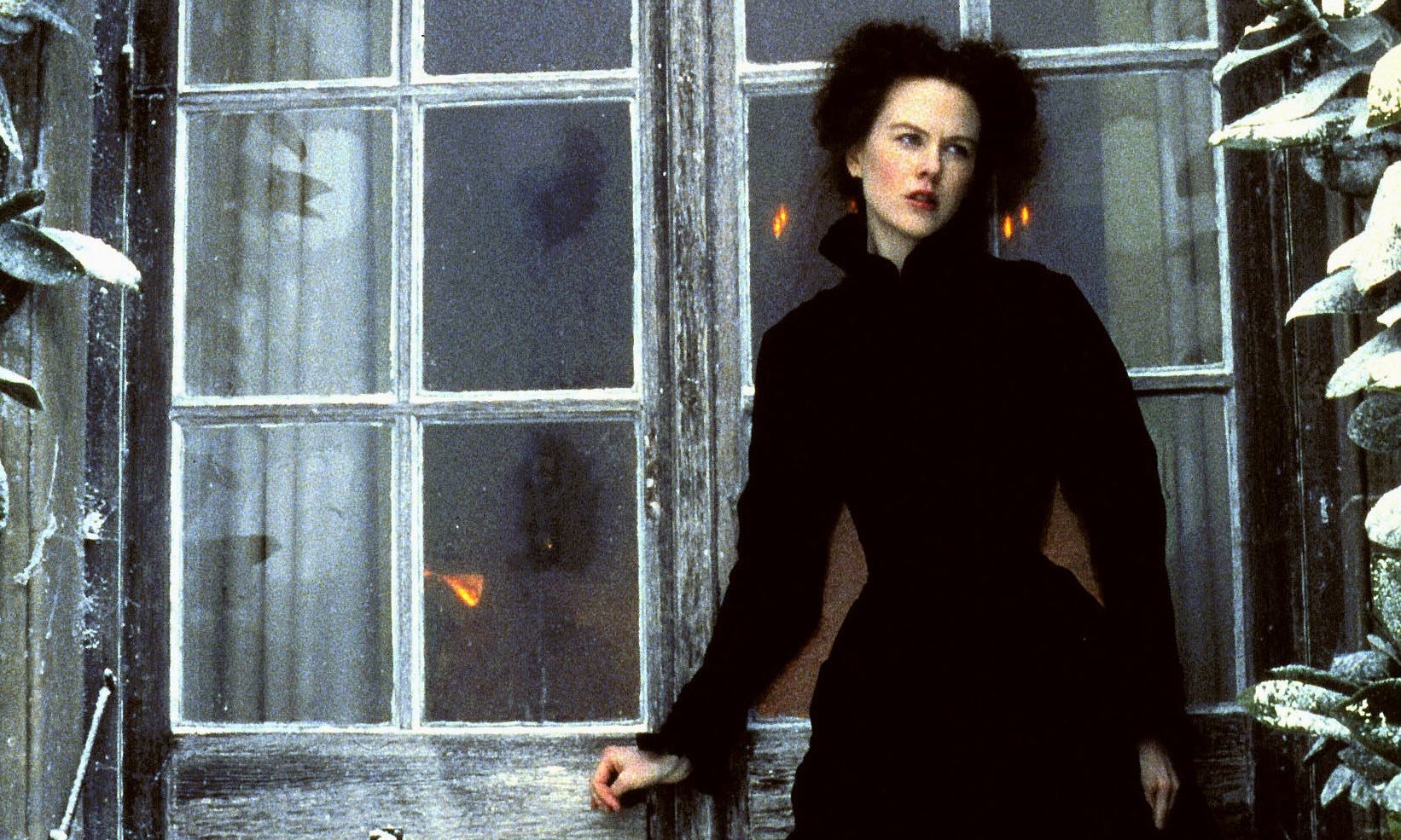

Take Charlotte Brontë's Villette, for example (a novel which, in my view, surpasses the more celebrated Jane Eyre). Its hero, the emotionally repressed Lucy Snowe - plain, lonely, angry and desperately striving to be self-sufficient - suffers a painful breakdown as a result of weeks of friendless solitariness during her time as an English teacher in a Belgian school. From my professional knowledge of breakdowns, Brontë's account is pin-sharp accurate and not only conveys a depth of experience (whether actual or imaginative) in its author, but acts as an objective correlative for those who have suffered in similar silence, conferring a critical lifeline, in the sense of not being quite alone in the world. Similarly, anyone who has undergone the wounding experience of family discord and alienation will find resonances in King Lear or Marilynne Robinson's Home.

Perhaps more surprisingly, and more radically, we may discover in a book shadow aspects of ourselves we have failed to acknowledge or recognise. Few of us imagine we are potential murderers: yet few reading Crime and Punishment can fail to enter the tortured consciousness of Raskolnikov, who believes in committing a murder he is acting justifiably, or fail to empathise with his anguished punishment of guilt. Dostoevsky illuminates, through the example of his character, what we might otherwise be too defended to comprehend: that our civilised selves may conceal a lethal armoury, potentially capable of atrocities, and that those who justify killing in the name of ideology are not as alien as we might care to believe.

So reading is not merely a diversion or distraction from present pain; it is also an enlarging of our universe, our sympathies, wisdom and experience. The act of entering into the consciousness of another being, another sex, or sexual preference, social group, political outlook or religious persuasion, allows a respite from private and parochial preoccupations. That widening of our concerns may entail entering another location, or period in history - or an arena of which we would otherwise be ignorant. Education, as people are never tired of repeating, is a process of leading out, which suggests another benefit: that in being led by reading into previously unknown territory, we learn.

Kommentar: See also: