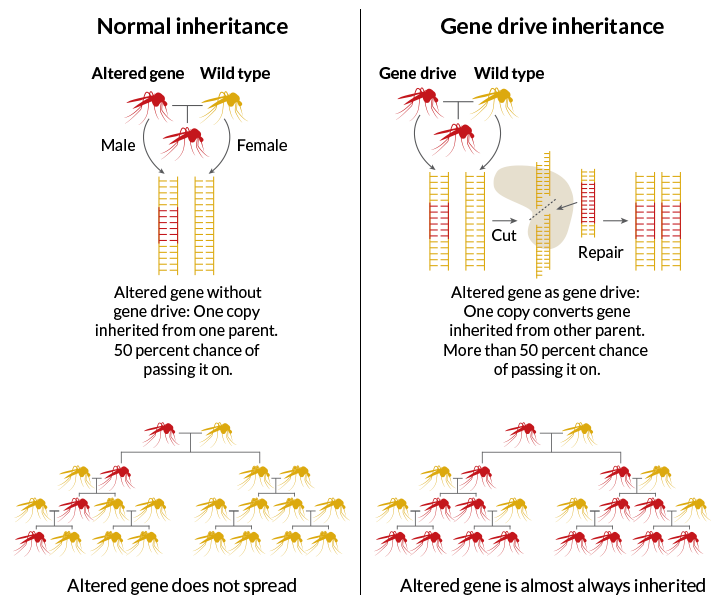

Standardudgaver af CRISPR gen drev (CRISP gene drives), som værktøjerne kaldes, kan få ændrede DNA til at brede sig til en population så let, at nogle få undslupne dyr eller planter kunne sprede ændringerne til et nyt område, forudsiger en computer simulation, der blev offentliggjort den 16. november på bioRxiv.org. Sådan en hændelse ville få ukendte, potentielt farlige følgevirkninger, siger et PLOS Biology papir pubiceret samme dag.

Vi er nødt til at komme ud af elfenbenstårnet og have en diskussion i det åbne, fordi miljøteknologi vil kunne påvirke alle, der lever i et område," siger Kevin Esvelt fra MIT, der er medforfatter på begge papirer, som beskæftiger sig med genetiske løsninger til miljøproblemer. Det, som er en plage et sted, kan være værdsat i et andet. Så at få tilladelse til at bruge gendrev kunne indbære, at man konsulterer folk i hele artens udbredelsesområde, hvad enten det er flere lande eller kontinenter.

Kommentar: Delvist oversat af Sott.net fra: CRISPR gene drives are too powerful to be used in the wild

Se også:

Reckless and unregulated: Biohackers are using CRISPR to edit their own DNA

Current CRISPR gene drive systems are likely to be highly invasive in wild populations

Researchers have constructed this kind of drive in yeast, a fruit fly and several mosquitoes, but none of the tools have been deployed yet in the wild (SN: 12/12/15, p. 16). Meanwhile, some researchers are already working to add brakes or off-switches into a new generation of gene drives.

The major concern is that current gene drives "are probably too powerful for us to seriously consider deploying in conservation," says geneticist Neil Gemmell of the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. Gemmell is a coauthor of the PLOS Biology paper.

This opinion could prove especially controversial in New Zealand. In 2016, the government resolved to protect the nation's imperiled biodiversity by exterminating invader rats, stoats and possums that are wreaking havoc on native species. Gene drives just might make that possible.

Comment: The government may want to consider setting traps. Scientists don't know enough about how genes or how they work to go fiddling with them.

Though warning of perils, the researchers also propose some solutions. A weaker system, which Esvelt calls a daisy drive, splits up components of the drive called guide RNAs. These guide RNAs direct the gene-editing machinery to its DNA target, where molecular scissors then snip and swap genetic material. As genes get inherited or not in the chancy jumbling of sexual reproduction, descendants in later generations become less likely to inherit all the spaced-apart pieces needed to operate the gene drive.

Esvelt's lab is working to create a daisy drive in two kinds of nematode worms and is looking at other species as well. Other labs are now working on tamer gene drives, too.

Anthony A. James of the University of California, Irvine says that the disease-carrying Anopheles mosquito species that he and his colleagues have equipped with gene drives are self-limiting. When females end up with two of the genes he's inserting, they don't "survive very well after they have fed on blood." Researchers are now raising these mosquitoes to see whether the genes spread and then dwindle away. "We don't need our genes to last forever," James says, "only long enough to contribute to getting rid of malaria."

Another lab's current version of disease-fighter mosquitoes already has a touch of the daisy. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes engineered with some built-in parts of the gene editor have their guide RNA split into two parts and put on different chromosomes, says molecular biologist Omar Akbari of the University of California, San Diego. Pictures of many weird mosquitoes created this way - all yellow or with three eyes or forked wings - attest to the fact that the drive system works. Akbari's research appears November 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Akbari is not very worried about the risk of accidentally wiping out disease-carrying mosquitoes. "A thousand children die every day," he says. It would be unethical not to use a tool that could lessen the loss, he says.

He does recognize that the case for caution could be different for other species. "A lot of pet owners would be sad," he says, if a gene drive went wrong and escaped worldwide during some future attempt to rid, say, Australia of its terribly destructive feral cats.

Læserkommentarer

dig vores Nyhedsbrev