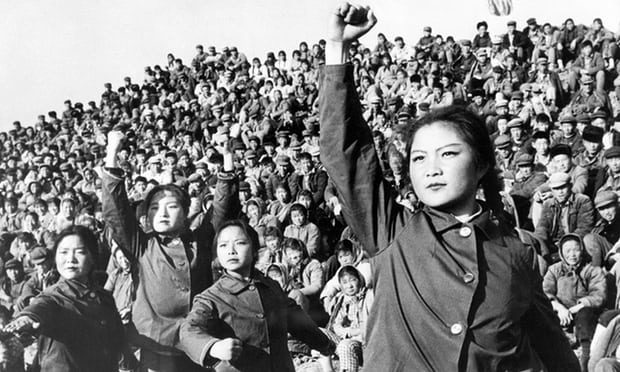

Tusinder af teenagers hænder strakte sig imod himlen da formand Mao trådte ned fra podiet på Tiananmen Square for at hilse på stødtropperne af hans revolution. Det var i sommeren 1966 og Maos store proletariske Kulturrevolution - en katastrofal politisk krampetrækning som ville kaste Kina ind i et årti af hjertesorg, ydmygelse og dødelig vold - var undervejs.

"Da vi så Mao Zedong vinke sin hånd, gik vi alle amok," genkalder Yu Xiangzhen, dengang en 13-årig skolepige, hvems farverige røde armbånd udmærkede hende som værende en af de millioner af loyale Røde Garder. "Vi råbte og skreg indtil vi ikke havde mere stemme tilbage.."

50 år efter starten på Kulturrevolutionen, i maj 1966, har Yu,som nu er 64 år, blogget sine erindringer om den periode i et forsøg på at forhindre at historien gentager sig.

Kinas kommunistiske ledere er forblevet tavse over jubilæet af den ødelæggende politiske mobilisering, som lærte vurderer krævede et sted mellem en og to millioner liv.

Men siden starten af dette år, har Yu forsøgt at bruge sin blog til at nedbryde denne væg af officiel stilhed omkring begivenhederne af denne blodige sommer.

Kommentar: Denne artikel er delvis oversat til dansk af Sott.net fra: Former Red Guard member recounts the horrors of China's Cultural Revolution

"If our descendants do not know the truth they will make the same mistakes again," she wrote in the introduction to her series of online reflections. "I want to use real experiences to prove that the Cultural Revolution was inhumane."

Even half a century on, Yu, a retired journalist, says she is still trying to fathom the horrors she witnessed that summer and to understand how she was radicalised into becoming one of Mao's "little generals".

"We became Red Guards [because] we all shared the belief that we would die to protect Chairman Mao," she says over a cup of tea in a Beijing cafe. "Even though it might be dangerous, that was absolutely what we had to do. Everything I had been taught told me that Chairman Mao was closer to us than our mums and dads. Without Chairman Mao, we would have nothing."

Yu's attempts to remember the mayhem of 1966 began in January, when she began composing short online dispatches on an ageing desktop computer at her home in China's capital.

"When I started to write, I didn't have a plan," she said. "I just wanted to write down what I experienced in those 10 years of cultural revolution. I didn't even have a title for my series of articles."

The former Red Guard decided to start at the very beginning, focusing her first essay on the closure of Beijing's primary schools, in May 1966: "For me, the Cultural Revolution started at that moment. [So] that was the first article I wrote," said Yu, who was a student at Beijing's Chongwen Number 49 middle school at the time.

Subsequent posts chronicle Yu's journeys through a world that was at once exhilarating, bewildering, comic and horrifying. She remembers the vicious persecution of her teachers, the lynching of suspected class enemies, the hysterical mass rallies, and how Red Guards roamed Beijing, setting upon those with supposedly counter-revolutionary footwear, clothing or hair.

"We thought that if you wore skinny trousers you were a monster," said Yu, recalling how scissors were used to lop the tips off pointy shoes, slice open excessively fashionable trousers or shear off locks of hair.

In one post, Yu recalls the excitement of boarding public buses with her Red Guard comrades and spending entire days reading extracts of Mao's Little Red Book to commuters. "It was quite fun," she recalled, leaning over the table in laughter. "I still remember the words in the book today. 'Revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery. It can't be done elegantly and gently.'"

"I believed it," Yu went on. "I thought Mao Zedong was great and that his words were great."

Other memories are more painful. As the summer of 1966 progressed, and a period of so-called "red terror" began, the thrill of having been let out of class and let loose on the Chinese capital faded and was replaced by an atmosphere of fear. Red Guards marauded across the city, ransacking and looting homes and staging public "struggle sessions" in which victims were savagely beaten, tortured and sometimes killed. At least 1,772 people are known to have been murdered in Beijing alone. Some targets committed suicide to escape the relentless persecution.

As violence engulfed the capital, an editorial in the Communist party journal, Red Flag, fanned the rapidly spreading flames. "The Red Guards have ruthlessly castigated, exposed, criticised and repudiated the decadent, reactionary culture of the bourgeoisie ... landing them in the position of rats running across the street and being chased by all," it read, according to Michael Schoenhals' seminal book on the period, China's Cultural Revolution.

One night Yu recalls being unable to sleep because of the ferocious beating being inflicted on one of her teachers. "Each time we fell asleep the screams woke us up. The screaming never stopped."

Later, towards the end of August, Yu recalls seeing a severely injured man dragging himself across the road towards her after he had apparently been subjected to a savage Red Guard attack. "There was blood all over his face," she said. "He looked like a ghost."

After fellow Red Guards ordered her to pummel a group of prisoners with a belt, Yu said she decided to flee. "God bless me, I didn't beat anyone back then. If I had beaten anyone how could I have lived with myself all these years?"

Yu's reflections on those days of chaos have earned praise from many readers. "People who stand up to tell the truth are so rare these days," one fan wrote on her blog. "So we look forward to more people like Teacher Yu coming out to tell the truth. I really appreciate what Teacher Yu has done."

But Yu admitted that her decision to revisit such a traumatic period had also provoked a backlash, with some critics accusing her of attempting to smear China's Communist party by dragging up a painful past. "You don't deserve to be Chinese!" wrote one commenter.

She denied her blog was intended as an attack on the country's rulers: "Some people say I am anti-Communist party. This is wrong. I'm not against the party at all. I want it to be great. I'm not interested in trying to open the old wounds of the Communist party."

Yu also shrugged off the concerns of friends and relatives - including her son - who warned that her outspokenness might land her in trouble.

"Some people have said the government will arrest me. 'If you stand up the government will silence you.' But I've never told a single lie. Everything I've said is based on the truth. They can arrest me but I've said nothing that isn't true." She said her blogging was partly therapeutic; a way of coming to terms with the shocking things she had seen. "I feel at peace when I write," she said.

But its main goal was to educate those who had not lived through the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and had not been allowed to learn about them at school, where the topic remains largely taboo.

Yu said memories of the period were now fading as many of those with first-hand knowledge of its turmoil entered their final years: "Telling the truth is the right thing to do. Only when people find the truth can they find the solution," she said. "This has happened in other countries. Why can't we do it here?"

Kommentar: "If our descendants do not know the truth they will make the same mistakes again..."

History in a nutshell.

Her cautionary words were timely because a similar leftist ideology is now giving rise to mass hysteria which bodes ill for Western civilization.