SOCHI - Udvisende en utrolig mangel på selvforståelse, så tweetede [avisen] the Guardians tidligere korrospondent til Moskva i søndags: "de engelske fans som jeg har mødt indtil videre i Volgograd er helt vilde med det. "Det er det modsatte af hvad vi forventede; alle har været utroligt velkommende. Sidste nat var fantastisk - (jeg/vi) kunne ikke ønske os en bedre start på en world cup tour".

Således lader det til at Shaun Walker, som for mange år havde det privilegie at fortolke Rusland til den næstmest besøgte lokale online nyhedskilde i Storbritannien (efter BBC), at være mystificeret af denne tilsyneladende modsætning. Men der er en enkel forklaring: Britiske mediers dækning af Rusland er ikke en nøjagtig skildring af landet.

Kommentar: Denne artikel er delvis oversat til dansk af Sott.net fra: Propaganda, meet Reality: English football fans discover Russia is rather different to media portrayal

Indeed, this is something I realized within a few weeks of arriving here, almost a decade ago now. After years of viewing the country through the prism of the UK and US press, my feelings were overwhelmingly negative. And, but for a random sequence of events which compelled me to visit, I doubt I'd ever have travelled to Russia, meaning I'd still hold those views today.

People who have never visited a particular country largely form their view of it from how it's presented in media they consume. This is why Hollywood has been such a powerful tool for the US, for instance. And it explains the British desire to continue pumping hundreds of millions of pounds into the BBC's international wing, despite painful austerity at home.

Of course, it's also why RT exists: this very network was established because Russians felt, with considerable justification, that western coverage of their country was unbalanced and unfair.

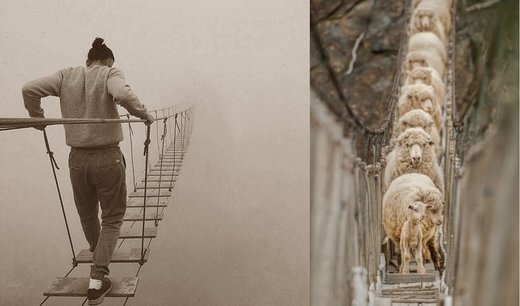

Together Forever

While US attitudes to Russia are simplistic, born both from distance and the Cold War mentality which permeates American discourse, British rhetoric is harder to explain. And the press appears to be seriously out-of-whack with the general public, who, in my experience, tend to have a more measured view of Russia.

If you use Twitter, you'll know the score. At every major Russia-related event the same bunch of journalists tweet out the same sarcastic drollery, egging each other on with the modern form of backslapping: likes and retweets.

The groupthink is staggering, but they lack the percipience to recognize the caricatures they've become. And, while Russia is my beat, it's naturally not restricted to this domain. Back home, the same sort of colloquy takes place daily: from political party conferences to business coverage.

Now, I've long wondered what's behind this behavior. Because having travelled all over Britain, I recognize a diverse country, where the general public is hardly conformist. Indeed, the postman in Edinburgh shares little of the worldview of the stockbroker in Surrey.

But the media increasingly sings off one hymn sheet: particularly when it comes to anything which threatens the establishment consensus. And the reason is pretty simple: these days, members of the press are overwhelmingly drawn from just two universities, Oxford and Cambridge, with the former outranking the latter.

Good Old Days

Traditionally, journalism was almost a working-class trade, where writers apprenticed on local newspapers, before catching a break on the national stage. Indeed, many notable journalists (John Pilger, to name one) didn't attend third-level at all. But now it appears outlets are recruiting directly from elite colleges. And this is particularly true on the Russia scene, where the majority of correspondents seem to be liberal arts majors (often in Russia studies) with no track record in journalism outside of this narrow focus: which is very unhealthy.

A weekend tweet from the Irish academic John O'Brennan, which showed how Guardian columnists arrived via Oxbridge, got me thinking. So, I decided to take a look at Oxford and Cambridge diaspora who cover Russia for British media, and it quickly became clear that graduates of the schools have near total control of the narrative.

Almost all the most prominent UK press commentators on Russia are linked by Oxbridge: including the likes of Anne Applebaum, Mark Galeotti, Ben Judah, Oliver Bullough and Luke Harding. Meanwhile, Edward Lucas is the son of a retired Oxford fellow and tutor, but he personally attended the LSE. And the same goes for a great many correspondents in Moscow, such as Walker himself.

British national media urgently needs more diversity. And it's not as simple as hiring extra black, Asian or LGBT workers. Instead, we need to see the trade return to its roots, where journalists trained up properly before being unleashed on the big leagues. And different educational and social backgrounds are properly represented.

If the current situation of Oxbridge capture continues, we will keep hearing how foreign lands visited by travelling Brits are the "opposite of what we expected." And that's a sad state of affairs, by any measure.

Læserkommentarer

dig vores Nyhedsbrev