Lidt ligesom dyrevelfærdsaktivister, der ejer en bøfhuskæde, kritiserede Disney filmstjernerne Kristin Bell og Keira Knightly for nyligt de dårlige eksempler, som de føler Disneyprincesserne bibringer piger. (Bell lagde stemme til Princess Anna i Disneys tegnefilm, Frozen, fra 2013, og Knightley har en hovedrolle som Sugar Plum Fairy i Disneys nye handlingsfilm, The Nutcracker and the Four Realms.) Knightley brugte endog sin promotion tour for Nutcracker til at afsløre, at hun havde forbudt visse Disneyfilm i sit eget hjem. Den lille havfrue, er én sådan forbudt title og Askepot er en anden - fordi, som Knightley forklarer, Askepot "venter på at en rig fyr skal redde hende."

Selvfølgelig er Knightley og Bell ikke alene med deres misfornøjelse. Der har i nogen tid været ført en krig mod "princessekulturen". Hele legioner af lyserødefobiske forældre er klar til at tage sørgedragten på, når som helst deres datter plager dem om at få én eller anden glitterbesmykket tingest i forretningen - som om det ville kaste en fortryllelse over hende og gøre hende til en undertrykt husmor i stedet for at kunne hjælpe hende på vej mod en naturvidenskabelig uddannelse.

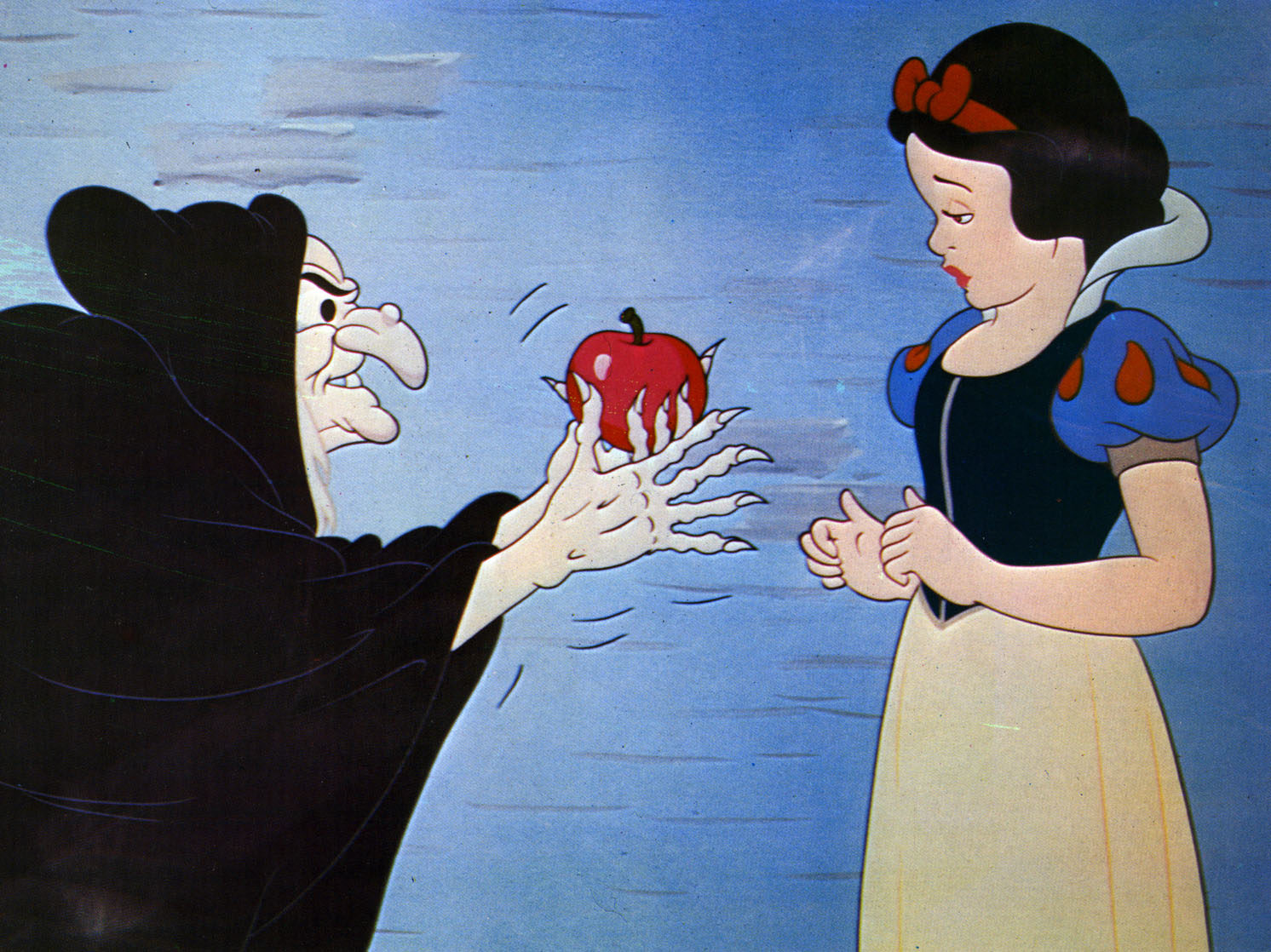

Bell har endog haft held til at se en #metoo i den scene, hvor prinsen giver Snehvide et opvågningskys, idet hun selv belærer sine døtre om, at "man ikke må kysse nogen, hvis de sover!" Ifølge denne logik bliver én af de smukkeste former for affektion, - når en mor kysser sit sovende barn - en upassende form for kontakt.

Dette er vanvidstænkning. Børn bliver ikke hjulpet af forældre, der projicere deres frygt på denne måde - altså at strække den situation at en prins forsigtig og uden bagtanke kysser en princesse tilbage til bevidsthed, til at betyde en godkendelse af at have sexuel omgang med en pige, der pga alkohol bliver bevidstløs ved en studenterfest.

Alligevel er det netop den form for hysteri, der bruges til at retfærdiggøres at slår alt det sjove væk, der er ved at se Disneys princessefilm. Kan du huske sjov? Det er et levn fra Amerika før 1990 - før legepladsen blev polstret, før der krævedes straffeattester for de forældrer, der står for skolens brødsalg og hvor eleverne i første klasse havde mere hjemmearbejde for, end jeg nogen sinde havde i gymnasiet.

Ironisk nok, og langt fra at forgifte unge kvinders sind, giver Disney princessehistorier - og deres foregængere i eventyrernes fiktive verden, værdifulde meddelelser, som forældre kunne bruge som udgangspunker for diskussioner med deres piger.

Kommentar: Delvist oversat af Sott.net fra Don't Deny Girls the Evolutionary Wisdom of Fairy-Tales and Princesses

Cinderella, for example, revolves around the perniciousness of what researchers call "female intrasexual competition" - the often-underhanded ways women compete with each other. While men evolved to be openly competitive, jockeying for position verbally or physically, female competition tends to be covert - indirect and sneaky - and often involves sabotaging another woman into being less appealing to men. Accordingly, in Cinderella, when the king throws a ball to find the prince a wife, the nasty stepsisters aren't at all "let the best woman win!" They assign Cinderella extra chores so she won't have time to pull together something to wear. (Mean Girls, the cartoon version, anyone?)

Sure, today, a woman can protect herself against even the biggest, scariest intruder with a gun or a taser - but that's not what our genes are telling us. We're living in modern times with an antique psychological operating system - adapted for the mating and survival problems of ancestral humans. It's often at a mismatch with our current environment.

Understanding this evolutionary mismatch helps women get why it's sometimes hard for them to speak up for themselves - to be direct and assertive. And identifying this as a problem handed them by evolution can help them override their reluctance - assert themselves, despite what feels "natural." Additionally, an evolutionary understanding of female competition can help women find other women's cruelty to them less mystifying. This, in turn, allows them to take such abuse less personally than if they buy into the myth of female society as one big supportive sisterhood.

Such myths have roots in academia. Academic feminists typically contend that culture alone is responsible for behavior. If pressed, they'll concede to some biological sex differences - but only below the neck. They deny that there could be psychological differences that evolved out of the physiological differences - and never mind all the evidence.

For example, evolutionary psychologists David Buss and David Schmitt explain - per surveys across cultures - that men and women evolved to have conflicting "sexual strategies." In general, "a long-term mating strategy" (commitment-seeking) would be optimal for women and a "short-term mating strategy" (the "hit it and quit it" model) would be optimal for men. (Guess which model is championed in princess movies?)

In almost all species, it's the female that gets pregnant and stuck with mouths to feed. So human women - like most females in other species - evolved to seek high-status male partners with an ability and willingness to invest.

This evolutionary imperative is supported by women's emotions, which anthropologist John Marshall Townsend explains, "act as an alarm system that urges women to test and evaluate investment and remedy deficiencies even when they try to be indifferent to investment." In Townsend's research, even when women wanted nothing but a one-time hookup with a guy, they often were surprised to wake up with worries like "Does he care about me?" and "Is sex all he was after?"

In other words, the allure of "princess culture" was created by evolution, not Disney. Over countless generations, our female ancestors most likely to have children who survived to pass on their genes were those whose emotions pushed them to hold out for commitment from a high status man - the hunter-gatherer version of that rich, hunky prince. A prince is a man who could have any woman, but - very importantly - he's bewitched by our girl, the modest but beautiful scullery maid. A man "bewitched" (or, in contemporary terms, "in love") is a man less likely to stray - so the princess story is actually a commitment fantasy.

Comment: <ideological possession> How utterly offensive... Commitment is a symbol of patriarchal oppression! </ideological possession>

Because of this, princess films can be the perfect foundation for parents of teen girls to have conversations about the realities of evolved female emotions in the mating sphere. A young woman who's been schooled (in simple terms) about evolutionary psychology is less likely to behave in ways that will leave her miserable - understanding that being "sexually liberated" might not make her emotionally liberated enough to have happy hookups with a string of Tinder randos.

As for the notion that watching classic princess films could be toxic to a girl's ambition, let's be real. Girls are being sent in droves to coding camp and are bombarded with slogans like "The future is female!" And young women - young women who grew up with princess films - now significantly outpace young men in college enrolment.

Children aren't idiots. They know that talking mirrors and pumpkins that Uber a girl to the royal prom aren't real, and they aren't having their autonomy brainwashed away by feature-length cartoons - just as none of us dropped anvils on the neighbor kids after watching Road Runner. Ultimately, these bans of princess movies are really about what's psychologically soothing for the parents, not what's good for children. Preventing children from watching princess films and other fantasy kid fare gives parents the illusion of control, the illusion that they're doing something meaningful and protective for their children.

Author and activist Lenore Skenazy urges parents to go "free range" - give their kids healthy independence, such as by letting them ride their bikes around the neighborhood without being accompanied by a rent-a-mercenary. I suggest parents also go psychologically free range. This means allowing children to watch classic Disney films instead of giving in to the ridiculous panic that their daughters will start seeing "princess" as a career option.

Stories give us insight into successful human behavior; they don't turn us into fleshy robots who act exactly as the characters do. Understanding this is essential, because if we instead succumb to the current paranoia, we'll have to remove much of the fiction from the high school curriculum - lest, say, Edgar Allan Poe's Tell-Tale Heart lead yet another generation of young readers to murder their roommates, cut them up, and stash them under the floorboards.

Amy Alkon sneers at "self-help" books and instead writes "science help" - translating research from across scientific disciplines into highly practical advice. Her new science-based book is Unf*ckology: A Field Guide to Living with Guts and Confidence. Follow Amy Alkon on Twitter at @amyalkon.

Læserkommentarer

dig vores Nyhedsbrev