Ved mere end en lejlighed har han lamenteret hvad han kalder "Den store australske stilhed" - forsømmelsen af "den vestlige kanon, litteraturen, poesien, musikken, historien og over alt andet, troen uden hvilken vores kultur og vores civllisation være utænkelig."

Abbott's forgænger, John Howard, er også kendt for at være en stærk forsvarer af den vestlige tradition og dets værdier, og han bekymrer sig ligeledes at vi er ved at tabe vore forbindelse med den: "Når vi tænker på vores civilisation, så mangler vi en integreret forståelse af bidraget fra de tidligere romere og grækere, rammerne som ligger til grund for hvad ofte er kaldt den jødisk-kristne etik."

Lidt længere væk, så har den tidligere britiske primeminister David Cameron prædiket om vigtigheden af kristne værdier i Storbritannien.

For knap så længe siden og måske ikke tiol gavn for sagen, så har Donald Trump hoppet på vognen. I et sjældent øjeblik af sammenhængenhed leverede Trump en tale forud for G20 topmødet i 2017 i Polen, tilskyndende til forsvaret af "vores værdier" og "vores civilisation."

Kommentar: Denne artikel er delvis oversat til dansk af Sott.net fra: An Eccentric Tradition: The Paradox of 'Western Values'

In this country, talk of Western or Judeo-Christian values has been backed by action. Abbott and Howard are both involved in the recently announced Ramsay Centre for Western Civilization - the result of an extraordinarily generous bequest of some billions of dollars from the late Paul Ramsay - whose mission is to promote the study of Western Civilization. That is a space that is being watched with great interest by indigent Arts Faculties and budget-conscious Vice-Chancellors.

While there is certainly something to be said for taking pride in our values and institutions, a fundamental paradox lies at the heart of this advocacy. The phrase "Western values" calls to mind a long moral tradition dating back to classical antiquity - the thought of the ancient Greeks, the traditions of Roman law, New Testament moral ideals. But the idea that there are such things as "Western values" cannot be found in any of these traditions themselves.

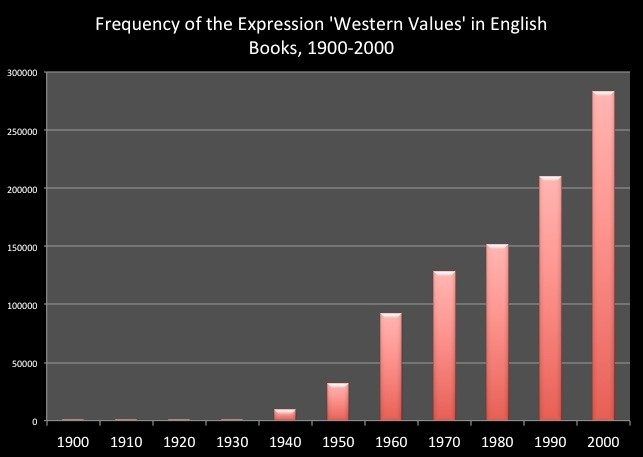

The specific concept of "Western values" is not itself part of the tradition to which it putatively refers. In fact, no one ever thought there was such a thing as "Western values" until the middle decades of the last century.

The relative novelty of the idea of Western values is attributable to two factors. First, all talk about moral or cultural values turns out to be a historically recent phenomenon. The expression "moral values" was not in use before the middle of the mid-nineteenth century. Second, and turning to the other component of our dual expression, the idea of "the West" - in the sense that Western values evokes - is also historically recent.

Ironically, for much of its history Europe sought to define its identity by drawing upon cultural norms and traditions that lay beyond its own geographical boundaries. "The West" is not an idea that those now regarded as instantiating it ever had about themselves.

The expression "Western values" does not appear in English until the middle of the twentieth century. Its entrance signals, at least partly, a significant soul-searching in the wake of the two World Wars that shattered any complacency about the moral superiority of Europe and the success of the Enlightenment project.

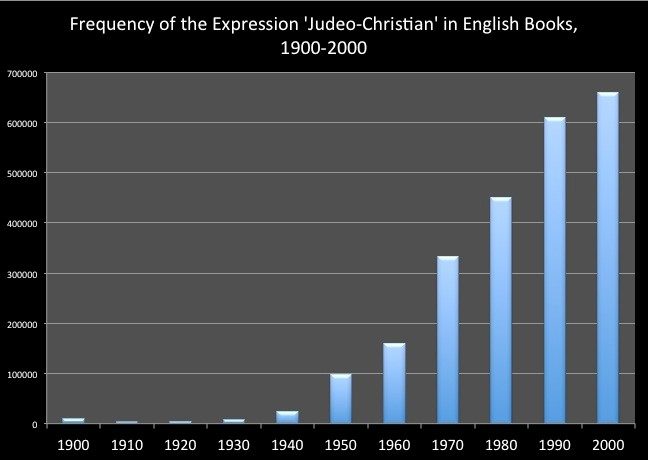

Its twin concept, "Judeo-Christian" values, has a similar trajectory, although its origins lie earlier in the nineteenth-century German "Tubingen School" of Protestant theology. The idea of a Jewish-Christian combination was subsequently adopted by nineteenth-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900,) who deployed the descriptor "judenchristlich" to denigrate what he regarded as an undesirable "Jewish-Christian" form of morality. The negative valence of this amalgam was to change following World War II with the sober realization that a virulent and deadly anti-Semitism had been nurtured in the bosom of a supposedly civilized West.

Like the idea of "Western values," the notion of "Judeo-Christian values" has enjoyed an increasing currency, and for much the same reason as the more generic expression.

The emergence of the idea of Western or Judeo-Christian values is thus itself an historical event, one that represents a particular way of thinking about a tradition or, perhaps more accurately, a way of constructing a particular tradition. Like all historical constructions, we can ask the question of whether or not it maps well onto the phenomenon that it purports to represent.

This late invention of Western values nicely illustrates the general paradox - the concept of a long tradition that arguably was never really a part of that tradition's own self-understanding.

How "Values" Displaced "Virtues"

One fundamental reason that there could not have been a traditional idea of Western values has to do with the fact that the central moral category in the West had been virtues rather than values. We search in vain in the utterances of ancient Greek philosophers, in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, the church fathers, medieval scholastics and early modern moral philosophers for an explicit terminology of "values."

In English, going back to the fourteenth century, the words "value" and "values" had denoted the material or monetary wealth of something. In the sixteenth century, this meaning was extended to particular measures of physical quantities.

The idea that there could be moral values came much later in the nineteenth century, originating in the United States, and bearing the connotations of measurable worth that attended the earlier senses of "value." Again, interestingly, in the philosophical context Friedrich Nietzsche is one of the first to use "values" (die Werte or Werthe) in this new sense.

This displacement of virtues by values is not an inconsequential matter of different words for the same thing. The gradual substitution of one for the other signals the modern quantification and commodification of morality. This trend is exemplified most conspicuously in the utilitarian moral tradition, which in the nineteenth century first gave us the idea of a "hedonistic calculus" - a literal toting up of the projected good produced by some act, minus the bad, to arrive at a net value of utility.

More generally the utilitarian idea was that ethics should not concern itself with the moral formation of the person, nor consider notions of duty or well-directed intentions, but focus instead on achieving particular outcomes. Consequences, ideally measurable ones, were elevated over character or intention. The focus thus shifted from the personal moral qualities of the individual to a focus on acts - or, in more sophisticated versions, rules.

At the terminus of this development we encounter the contemporary mania for measurement of outcomes, along with declarations of "corporate values." Values in this mode are imagined to serve the specific goals of the organization, often quite independently of the question as to whether those goals themselves might be good.

Needless to say, these public proclamations of values are not only different from the preceding practices of inculcating virtues, but are often antithetical to them. Whereas "virtues" are necessarily understood as personal qualities, and are not so much defined and articulated as practised, "values," by way of contrast, can be set out in propositional form. Corporate values can thus be enumerated as dot points in glossy publications and on home pages. There are even websites designed to assist corporations in the enumeration of a marketable set of values. One of these helpfully suggests that all one needs to create a core values list is 50 post-it notes, a pen, and "the core values list."

No requirement, then, for Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, Aquinas's Treatise on Virtues, or Kant's second Critique.

Unlike duties, to which one is in some sense already bound, or virtues, which represent the embodiment of a gradual process of a natural moral formation, values understood in this mode can be freely chosen. There is a values market. Curiously, then, the values adopted by an individual on a particular issue can now be a source of disapprobation on the part of others, because values are seen to be a matter of choice rather than irresistible conviction.

This situation, needless to say, is at odds with the assumptions of many champions of Western values, for whom values are grounded in a particular tradition. The general point is that "values" might not be the best category for describing what is supposed to be the deep-rooted moral tradition of the West.

It is also relevant that it was the historical demise of the virtues - eloquently described in Alasdair MacIntyre's classic After Virtue - that occasioned the disintegration of Europe's common moral language, giving rise to different and arguably, incompatible, ways of grounding morality. From the seventeenth century onwards, we can identify not just varying sets of moral and religious commitments, but a growing disagreement about how moral positions are to be justified and even what would count as a moral commitment.

A full account of the ascendancy of values talk would require a more comprehensive account of the history of modern moral philosophy than can be given here. For now, we can simply note that the very idea of "moral values" is historically recent and somewhat at odds with long-standing Western convictions about the good life and how to live it. The earlier tradition was to do with cultivating virtues that are aligned with a particular conception of the good.

But one thing that clearly follows is that a disinterested history of the Western moral reflection is unlikely to promote the recovery of a set of core "values," but will rather show that Western ethical concerns have traditionally been conceived in quite different terms.

In short, if we look to the past in order to recover some long-standing and deep Western moral tradition, what we will discover is virtues rather than values. And once values appear on the scene not only do we search in vain for agreement about what they should be, we also encounter increasingly incommensurable understandings about what it is that morality consists in.

The Eccentric Culture of "the West"

So much, then, for values. What about the second element of the conjunction: Western. Here, again, as a way of characterising Christendom or European culture, this term emerges relatively late, in the nineteenth century.

Admittedly, there is a long-standing idea of a variously different, hostile, or exotic "East" that goes back a very long way. In the Persian Wars of the fifth century BC, when the Greeks achieved independence from Persia, we already have a conception of an agonistic and alien "East." But curiously this very early idea of the East does not seem to have given rise to any strong sense of a counterpart "West."

From classical antiquity onwards, the "East" was itself understood in a variety of different ways. For the Greeks, the East was the area east of the Mediterranean basin. An East-West division, while not necessarily understood in the same geographical terms, was further consolidated with the administrative division of the Roman Empire in late antiquity under successive emperors from Diocletian (late third century) onwards. This division was followed by the Great Schism (1054) in Christianity, which produced the division of Catholic and Eastern Orthodox.

Crucially, throughout the middle ages and into early modernity, Western European identity can be characterised in terms of its dependency upon, and perceived inferiority to, traditions that lay beyond its geographical and temporal borders. The French historian Remi Brague has thus advanced an intriguing argument to the effect that what was distinctive about Christian Europe for much of its history is the way in which it stands in a kind of secondary relation to previous cultures - in particular, those of ancient Palestine and Greece.

In both cases, the Christian West was indebted to something both prior to and outside itself.

This specific form of indebtedness becomes apparent when we contrast Western Europe with Islamic societies. At the risk of overgeneralization, we might say that medieval Islamic cultures, while open to outside influence, often completely absorbed what it required from preceding traditions - Greek, Hebrew and Christian - but discarded the remainder. Europe, however, never sought fully to incorporate the Greek or Jewish cultures that preceded it. A key marker of this difference is the way in which highly sophisticated Islamic cultures of the middle ages translated Greek and Latin texts into Arabic, but then showed little interest in preserving the originals.

If we compare this to Christian attitudes, even going back to the first century, we see first of all an interest in preserving the Hebrew bible intact as a canonical document. Early Christian movements that sought to declare the Hebrew bible redundant were thus regarded as heretical. Again, by comparison, Islam incorporated elements of the other two "religions of the book" - Judaism and Christianity - into the Qur'an, but had no interest in preserving the Torah or the New Testament as such. This precluded any possibility within Islamic societies of an ongoing, albeit virtual, dialogue with the cultures that preceded it. Arguably, this deprived it of sources of revival and renewal. (I should make clear that am not arguing here that Islam needs "a reformation." That confused claim is motivated by a wholly different set of considerations.)

By way of contrast, in Europe we see a series of renaissances, reformations and intellectual revolutions that drew upon sources outside itself. Europe was thus able to return again and again to the canonical texts of ancient Greece and Palestine - both of which lay beyond the historical boundaries of the Latin West - in order to fuel its own internal renewal. European intellectual culture was thus distinguished by ongoing conversations with cultures that preceded it and which for a considerable period of time it regarded as superior to itself. Again, crucially, these cultures were not absorbed into the West, but preserved intact as potential conversation partners.

It follows that until the modern period, rather than representing an ossified conservative tradition, Western Europe had been something of a work in progress. For most of its history it was outward-looking and, in a sense, at an intellectual level, intrinsically "multicultural." No culture, according to Remi Brague, was so little centred on itself and so interested in others. Europe, in this sense, has an "eccentric" culture, because historically it found its centre outside itself. Rather than a repository of specific values it was an attitude: a resolution "to be a container, open to the universal."

The specific episodes that mark Europe's periods of renewal are well known. The twelfth-century renaissance saw the European rediscovery of Aristotle (mediated by Arabic sources) and the rise of the medieval universities. If we take one of the leading thinkers of the medieval period, Thomas Aquinas, as an example, we observe that his works include eleven commentaries on Aristotle and five commentaries on books of the Hebrew bible. Even his most famous systematic work, the Summa theologiae, exemplifies an ongoing dialogue with the past, with topics set out as open questions, and various answers being provided by classical, biblical and patristic authorities.

The High Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries witnessed a much more comprehensive recovery of ancient sources, including new literary and historical sources, often now in the original Greek, along with a renewed interest in classical forms of art and architecture. The Renaissance was followed by the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation. Renaissance humanists shared with the Protestant reformation the motto ad fontes ("back to the sources"), again looking to the past to provide the resources for renewal. It would be difficult to overestimate how important textual and linguistic skills were to these transformations. Such skills remain crucial to the thriving of humanities, which in turn act as curators of the resources represented by the past.

The Enlightenment's Rejection of Tradition

It is true that some reform movements in the West employed the rhetoric of a repudiation of the past. This makes for another potential paradox: a Western tradition based upon a rejection of tradition.

Rene Descartes, whose work is often thought to mark the beginning of modern Western philosophy, thus claimed to abjure all traditions, turning away from the study of letters and resolving to derive knowledge only from "what can be found in myself or else in the great book of the world." But the inward turn to the self had long been part of the tradition he was supposedly disavowing, going back to the famous Greek motto "know thyself," with subsequent recommendations from Augustine and Petrarch. Descartes's famous Cogito ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am") thus echoes Augustine's si fallor, sum ("if I am mistaken, I exist") and his arguments for the existence of God are indebted to the medieval scholastic thinker Anselm of Canterbury. Descartes's supposedly novel reorientation towards the natural world also drew strongly upon historical precedents.

Surprising as it may seem, even the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, which Descartes helped inaugurate, found inspiration in ancient scientific theories, resurrecting features of Epicurean natural philosophy and opposing them to a long-standing Aristotelianism. Before the appropriation of ancient atomism by such figures as Descartes and Pierre Gassendi, Copernicanism was understood as a revival of "Pythagoreanism." Platonist philosopher Henry More found Descartes's cosmology in the book of Genesis. Even Isaac Newton assumed that the laws of gravitation had been known and represented in ancient hermetic writings, and spent more time studying ancient texts than he devoted to his scientific pursuits.

The cultural modesty of Europe, along with its self-conscious indebtedness to others, began to dissipate in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when we start to see a new-found confidence in Western superiority and distinctiveness. The Enlightenment was partly responsible for this, with its exponents lauding the powers of instrumental reason and scientific experiment while at the same time assuming Europe to be the unique site of reason's ultimate triumph. Eighteenth-century French philosophes appropriated the success of the sciences as part of their story of the march of reason, although this progressive component had been at best incipient in the self-understandings of the progenitors of modern science.

In present discussions of Western values, "the Enlightenment" is routinely invoked as a special period in our past, the ethos of which we urgently need to import into the present. But ironically, in relation to Western values projects, the chief agents of the Enlightenment actively sought to sever their own ties with the past and disguise the historical trail that showed that period's deep indebtedness to earlier religious and philosophical traditions. Much present-day deference to the Enlightenment and adulation of its imagined ideals proceeds not from insight into the historical realities of the period, or any understanding of the plural forms of Enlightenment, but from a naive acceptance of the crude propaganda of French philosophes.

"The West" as the End of History

The growing self-confidence of Europe can also be attributed to the rise of a new historical consciousness and the emergence of the social sciences. The philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) exemplifies the former tendency in his Philosophy of World History, where he maintains that European civilization is the unique end-product of the unfolding of history.

This was a theme with many variations. The nascent social sciences of the nineteenth century also enshrined the cultural superiority of Europe by proposing progressive stages of social evolution, typically beginning with primitive religious or magical phases, and moving ineluctably towards scientific, rational phases, best represented by an increasingly secularized Western Europe. The philosopher and social scientist Auguste Comte (1798-1857), who popularised the term "sociology," set out three stages of the development of human knowledge - theological, metaphysical and scientific. Similar tripartite schemas of social evolution were proposed by pioneering anthropologists James Fraser and E.B. Tylor.

Comte is doubly significant for our story, since he first introduced the modern idea of the "the West." The term was certainly in use before this time, but was typically used interchangeably with "Europe." As historian Georgio Varouxakis has recently shown, Comte sought to describe a new socio-political category that would take in the Americas and Australasia. Europe included nations that were not sufficiently in "the vanguard of Humanity," while Christendom had equally undesirable religious connotations: hence the new ideas of l'Occident and occidentalite.

What Comte attempted to do with his new vision of the transnational "West" was a reorganization of the world order which would see the demise of the colonial powers and the establishment of a new "Western Republic." This elite republic would serve as a model for the rest of the world, assisting less advanced nations to develop toward the scientific or "positive" end-goal at which it had already arrived. The idea of the West was subsequently taken up by Anglophone writers and put to various uses. But common to most understandings was a notional superiority of what the West represented.

One of the more portentous consequences of the birth of "the West" as a category was the creation of a counterpart "Muslim world" - an updated reification and refinement of the long-standing "Orient." Ironically, the currency of this notion was bolstered by Muslim intellectuals who, rather than refute the implausible construct of a unified Islamic civilization, embraced the idea with a view to arguing for its positive contributions to global progress and for its ultimate compatibility with modernity. In doing so they glossed over the plurality of practices and beliefs in this imagined Muslim world and de-emphasised what they believed to be its more backward features in the interests of promoting Muslim solidarity and resistance to Western assertions of Muslim inferiority. As Cemil Aydin has remarked:

"...the nineteenth-century goal of positioning Islam as enlightened and tolerant - and therefore Muslims as racially equal to their Western overlords - produced the notion of Islam in the abstract, providing the core substance of Muslim reformism and pan-Islamic thought in the early twentieth century."In this new context, "Judeo-Christian" takes on yet another meaning. In its twentieth-century Anglo-American uses it was intended to be inclusive of Jews. Now it is routinely used, implicitly or explicitly, to exclude Muslims. This contrasts with the alternative characterizations of "Abrahamic faiths" or "religions of the book," which stress the common features of the three monotheistic Western traditions.

"The West," although variously conceived, informs diagnoses about the present state of global affairs and proposals for how the values that it represents are to be preserved and promoted. More sanguine visions of the future imagine that, through some inexorable historical law, other cultures will eventually "catch up" to the West, through a natural progression towards the end-state that the West is thought to have accomplished. Francis Fukuyama's The End of History and the Last Man represented a restatement of this position, which holds in essence that secular, capitalist, liberal democracy is the only game in town.

On this model, the solution to cultural conflict is to accelerate the modernization and secularization of troublesome cultures that lag behind the West. This is the logic behind the classification of Islamic Fundamentalism as "medieval," or the observation that Islam needs to undergo its own "reformation."

More pessimistic readings of the current stage of affairs imagine various threats to the integrity of the West. Whereas Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West suggested that all cultures have a natural life-span, the new harbingers of the West's demise point to dangers posed by internal deviations from an imagined tradition or external threats from competing cultural complexes. These tendencies are best represented by Samuel Huntington and his well-known Clash of Civilizations thesis. In this version of events, Western civilization is imperilled by civilizations with different values, either because of the external security threats they pose, or because the liberal West too readily welcomes immigration from populations that bring with them inimical values. While external threats comprised the main focus of the Clash of Civilizations book, Huntington articulates the internal threat in a subsequent book, Who Are We?

Analyses such as these seem to draw upon dispassionate historical analysis. But, in fact, their prognostications arise out of the uncritical deployment of a seductive, but highly contentious vocabulary. "The West" and its counterpart "the Muslim World" are not neutral analytical categories that offer disinterested descriptions of existing states of affairs: they are expressions that were framed with particular purposes in mind and come pre-loaded with political programmes. Their use predetermines our understanding of history and delimits the range of possible responses to present and future events.

Comment: Another loaded word is 'civilization', also invented in 18th century France. (See The Empire of Civilization by Brett Bowden)

All of this suggests that a robust study of the history of "the Western tradition" should include careful scrutiny of the various ways in which, over the centuries, Western identity has been constructed and understood.

A Rich and Varied Past

European settlers in Australia are indeed heirs to a particular tradition (or related traditions). But that European heritage cannot simply be reduced to a core set of "Western values." For much of its history, Europe was focused on virtues rather than values, and was characterised by an openness to past cultures that were essentially non-European.

Given the revolutionary potential of this outward and backward-looking perspective, it is curious that the invocation of a classical and Christian heritage these days is regarded as a hallmark of moral and political conservatism.

When we look closely at the relevant history, this identification seems incongruous. Harvard Classicist Bernard Knox gets it exactly right when he tells us how strange it is to find classical Greeks "assailed as emblems of reactionary conservatism, of enforced conformity." In fact, as he points out, "their role in the history of the West has always been innovative, sometimes indeed subversive, even revolutionary." Something similar can be said of central elements of the Christian tradition which have provided the motivation for radical social and political reforms.

I fully endorse the sentiment that we need a greater familiarity with our own cultural, religious and intellectual past. But the study of what we might call "the Western tradition" will not turn out to be as comforting to advocates of conservative moral and political values as they might imagine. We will see that there is no neat alignment of the study of tradition with traditionalism and political conservatism. Rather the relevant history will bear witness to an ongoing conversation and a continuous dialogue with other cultural traditions. That dialogue was as robust in the middle ages and early modern period as in the post-Enlightenment era.

It is here that the great potential of a "Western tradition" project lies - not in the fetishizing of some imagined canon of fixed values, but in the preservation of a rich and varied past that can continue to serve as on ongoing challenge to the priorities and "values" of the present.

And it follows that it is not just long-gone cultures that can play this role, but also those that we encounter in the contemporary world. Knowledge of our own cultural traditions can be deeply enriched by perspectives gained from knowledge of other cultures. As the great comparative linguist and religionist Max Mueller succinctly put it (in the idiom of his time), "he who knows one, knows none."

About the author

Peter Harrison is an Australian Laureate Fellow and Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Queensland. This article is an edited version of an IASH Public Lecture, first delivered on 30 August, 2017 at the University of Queensland. His most recent books are The Territories of Science and Religion and Narratives of Secularization.

Læserkommentarer

dig vores Nyhedsbrev