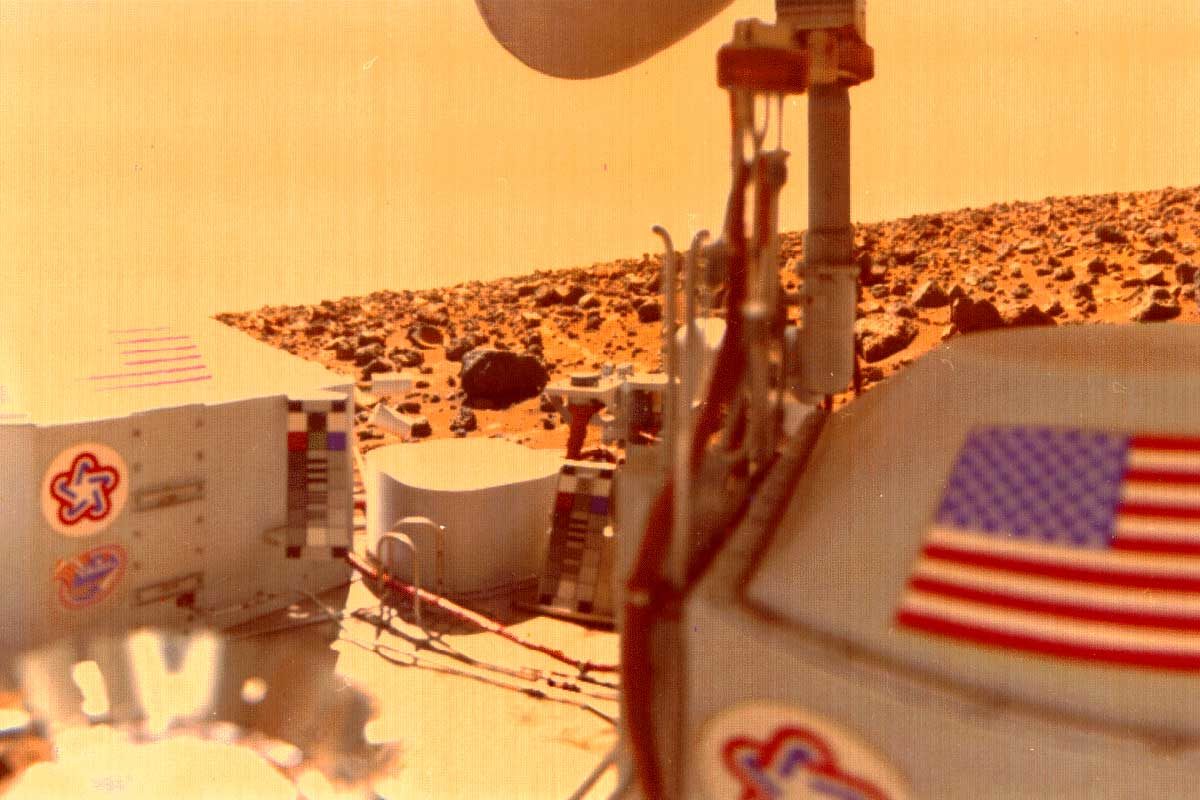

I 1976 gennemførte NASAs tvilling Viking-landere de første eksperimenter, der søgte efter organisk stof på den røde planet. Forskere havde længe vidst, at alle planeter modtager en konstant regn af kulstofrige mikrometeoritter og støv fra rummet, hvilket betyder, at Mars skulle kvæles i organiske molekyler. Men vikingelanderne fandt intet, hvilket efterlod forskerne i stor forundring.

"Det var bare helt uventet og uforeneligt med det, vi vidste," siger Chris McKay ved NASAs Ames Research Center i Mountain View, Californien.

Hjemsøgt af Mars's manglende molekyler foreslog forskere den ene forklaring efter den anden, men ingen syntes at passe - indtil endnu en sonde kom i spil.

Phoenix rising

In 2008, NASA's Phoenix lander found an odd salt near Mars's North Pole, known as perchlorate. On Earth, it is used for rocket fuel and fireworks because it becomes explosive at high temperatures.

That is not a problem on the surface of Mars, which is relatively chilly, but in order to search for organics, the Viking landers roasted samples of Martian soil to sniff out its constituent molecules. With perchlorate in that soil, these experiments would have literally burned any organics, thus masking their presence.

After this discovery, McKay and a few colleagues regained their conviction that organics were indeed present on Mars. "Suddenly you get some new insight and you realise that everything you thought was wrong," he says.

But the field was divided. Some argued that the Martian surface contained organics while others were convinced it was sterile.

It wasn't until Curiosity's latest discoveries that researchers have been able to spot these compounds, as well as finally vindicate the rover's predecessor. The key is that along with the complex organic molecules, Curiosity also found chlorobenzene.

This molecule - with six carbon atoms in a honeycomb shape, plus one chlorine atom and five hydrogen atoms attached at the corners - is produced when carbon molecules burn with perchlorate. As such, it is indirect evidence that there are organics on Mars and should have been seen by Viking.

With that in mind, Melissa Guzman at the LATMOS research centre in France, McKay and their colleagues dug through the Viking data only to find that it too had spotted chlorobenzene, probably from burning organic material.

Guzman remains cautious, saying she is not yet 100 per cent convinced that the chlorobenzene formed as a result of burning Martian organics, rather than stowaways from Earth, but others consider the case closed.

Daniel Glavin at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland, who was not involved in the study, says the compound is so complex that it must have formed from Mars's missing molecules.

"This paper really seals the deal," he says. He thinks the research will finally convince people that Viking didn't come up empty after all. Taken with the findings from Curiosity, it suggests organics exist at more than one site on Mars - so the planet may be smothered in them after all.

Journal reference: Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, DOI: 10.1029/2018JE005544

Article amended on 16 July 2018

Correction:We corrected the composition of chlorobenzene.

A shorter version of this article was published in New Scientist magazine on 5 May 2018

Kommentar: The evidence suggest that space is teaming with life: