© sittingwithsorrow.typepad.com

Én af Frida Kahlos mest berømte selvportrætter afbilleder hende i et hospital nøgen og blødende, forbundet med et net af røde vener til svævende objekter som omfatter en snegl, en blomst og et foster.

Henry Ford Hospital, det 1932 surrealistiske maleri, er en kraftfuld kunstnerisk gengivelse af Kahlos anden abort.

Kahlo skrev i sine dagbøger at maleriet "bærer i sig en meddelelse af smerte." Maleren var kendt for at kanalisere erfaringen af mange aborter, børnelammelse og et antal af andre ulykker i sine ikoniske selvportrætter, og en virkelig forståelse af hendes arbejder kræver en vis viden om den lidelse, der motiverede den.

Fænomenet med kunst født af modgang kan ses ikke kun i livet af berømte skabere, men også i laboratoriet. I de sidste 20 år er psykologer begyndt at studere posttraumatisk udvikling, som er blevet beskrevet i mere en 300 videnskabelige studier.

Udtrykket post-traumatisk vækst blev formuleret i 1990erne af psykologerne Richard Tedeschi og Lawrence Calhoun for at beskrive tilfælde af individer, som erfarede dybe transformationer i takt med, at de lærte at håndtere forskellige typer af trauma og udfordrende livsomstændigheder. Forskningen har vist, at op til 70 procent af traumaoverlevende beretter om en positiv psykologisk vækst.

Vækst og trauma kan tage flere forskellige former herunder større værdsættelse af livet, herunder større værdsættelse af livet, identificering af nye muligheder for ens liv, mere tilfredsstillende mellemmenneskelige relationer, et rigere spirituelt liv og en forbindelse til noget større end en selv og en oplevelse af personlig styrke. En kamp med kræft, for eksempel, kan lede til en fornyet taknemmelighed over for ens familie, mens en nærdødsoplevelse kan være katalysatoren for forbindelse med en mere spirituel side af livet.

Psykologer har fundet, at erfaringer af trauma også almindeligvis leder til øget empati og altruisme, og en motivation til at handle til gavn for andre.

Life After TraumaSo how is it that out of suffering we can come to not only return to our baseline state but to deeply improve our lives? And why are some people crushed by trauma, while others thrive? Tedeschi and Calhoun explain that post-traumatic growth, in whatever form it takes, can be "an experience of improvement that is for some persons deeply profound."

The two University of North Carolina researchers created the most accepted model of post-traumatic growth to date, which holds that people naturally develop and rely on a set of beliefs and assumptions that they've formed about the world, and in order for growth to occur after a trauma, the traumatic event must deeply challenge those beliefs. By Tedeschi and Calhoun's account,

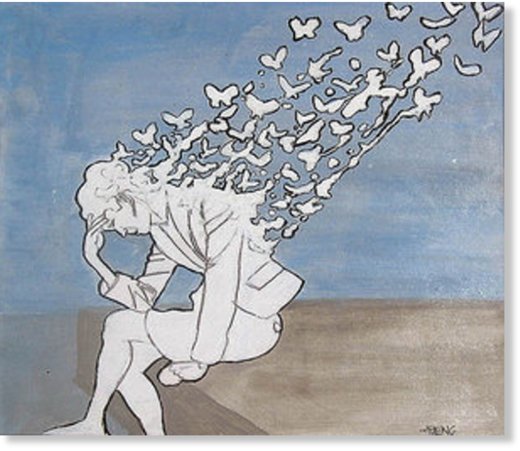

the way that trauma shatters our worldviews, beliefs, and identities is like an earthquake—even our most foundational structures of thought and belief crumble to pieces from the magnitude of the impact. We are shaken, almost literally, from our ordinary perception, and left to rebuild ourselves and our worlds. The more we are shaken, the more we must let go of our former selves and assumptions, and begin again from the ground up."A psychologically seismic event can severely shake, threaten, or reduce to rubble many of the schematic structures that have guided understanding, decision making, and meaningfulness," they write.

The physical rebuilding of a city that takes place after an earthquake can be likened to the cognitive processing and restructuring that an individual experiences in the wake of a trauma. Once the most foundational structures of the self have been shaken, we are in a position to pursue new—and perhaps creative—opportunities.

The "rebuilding" process looks something like this: After a traumatic event, such as a serious illness or loss of a loved one, individuals intensely process the event—they're constantly thinking about what happened, and usually with strong emotional reactions.

It's important to note that sadness, grief, anger, and anxiety, of course, are common responses to trauma,

and growth generally occurs alongside these challenging emotions—not in place of them. The process of growth can be seen as a way to adapt to extremely adverse circumstances and to gain an understanding of both the trauma and its negative psychological impact.

Rebuilding can be an incredibly challenging process.

The work of growth requires detaching from and releasing deep-seated goals, identities, and assumptions, while also building up new goals, schemas, and meanings. It can be grueling, excruciating, and exhausting. But it can open the door to a new life. The trauma survivor begins to see herself as a thriver and revises her self-definition to accommodate her new strength and wisdom. She may reconstruct herself in a way that feels more authentic and true to her inner self and to her own unique path in life.

Creative Growth Out of loss, there can be creative gain. Of course, it's important to note that trauma is neither necessary nor sufficient for creativity. Experiences of trauma in any form are tragic and psychologically devastating, no matter what type of creative growth occurs in their aftermath. These experiences can just as easily lead to long-term loss as gain. Indeed, loss and gain, suffering and growth, often co‑occur.

Because adverse events force us to reexamine our beliefs and priorities, they can help us break out of habitual ways of thinking and thereby boost creativity, explains Marie Forgeard, a psychologist at McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School, who has done extensive research into post-traumatic growth and creativity.

"We're forced to reconsider things we took for granted, and we're forced to think about new things," says Forgeard. "Adverse events can be so powerful that they force us to think about questions we never would have thought of otherwise."

Creativity can even become a sort of coping mechanism after a difficult experience. Some people might find that the experience of adversity forces them to question their basic assumptions about the world and therefore to think more creatively. Others might find that they have a new (or renewed) motivation to spend time engaged in creative activities. And others who already had a strong interest in creative work may turn to creativity as the main way of rebuilding their lives.

Kommentar: Der kan være en forbindelse mellem nogle af ideerne i ovennævnte artikel og følgende: Dabrowski's Theory of Positive Disintegration: Wandering upward to a new you